This column is an opinion by Brian Bird, an assistant professor at the Peter A. Allard School of Law at the University of British Columbia. For more information about CBC’s Opinion section, please see the FAQ.

If you’d never heard of Ruth Bader Ginsburg before her recent passing, you could be forgiven for thinking the media had got it wrong in referring to her as a judge. With labels like fighter for justice, feminist icon and liberal lion, you might wonder if she was in fact a politician or civil rights advocate.

Ginsburg was the latter during her pre-judicial career. As general counsel for the American Civil Liberties Union, she made a large and lasting mark on the law of the United States, especially concerning equality for women.

But Ginsburg was indeed a judge for the final 40 years of her life. She was a person of immense intellect and interior strength, and indisputably a “jurist of historic statute” and a “tireless and resolute champion of justice” as John Roberts, Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, wrote in announcing Ginsburg’s death.

The blurring of Ginsburg’s legal advocacy and her work as a judge on the U.S. Supreme Court says much about how judges are viewed today in democratic countries like Canada and the United States.

There is a debate over the role that judges should play in shaping and defining fundamental rights, freedoms, and the basic values of a society. It’s a debate that is vigorously renewed with every vacancy on a Supreme Court, and the recently completed confirmation process of U.S. Justice Amy Coney Barrett, Justice Ginsburg’s newly minted successor, was no exception.

Judges, especially high court judges, are currently considered by many citizens to be providers (rather than simply protectors) of legal rights and benefits, even though this is a role historically reserved in both Canada and the U.S. for legislatures rather than the judiciary.

Some judges clearly feel this way, too.

In a tribute, Justice Rosalie Abella of Canada’s Supreme Court described Ginsburg as “a reminder not only that justice is of the people and for the people, but that judges, at their best, will deliver it to them with fearless wisdom and transcendent hope.” Elsewhere, Justice Abella has described a high court as, “the final adjudicator of which contested values in a society should triumph,” a comment that sparked controversy for arguably exaggerating the powers of a Supreme Court.

In fairness to Justice Abella, how can judges possibly set aside their moral outlook when determining the scope, content, and limitation of rights and freedoms guaranteed by a constitutional bill of rights such as the Charter?

The reality is that judges must employ moral reasoning in these cases – but only to an extent. Judges must take the text of the Charter as they find it; they do not have a normative or interpretative blank cheque.

As Justice Bertha Wilson put it, the “basic theory underlying the Charter” is that the state – an entity that includes courts – will “respect choices made by individuals and, to the greatest extent possible, will avoid subordinating these choices to any one conception of the good life.”

In other words, the Charter is not a vehicle for courts to achieve social progress. It is, first and foremost, a shield from state overreach.

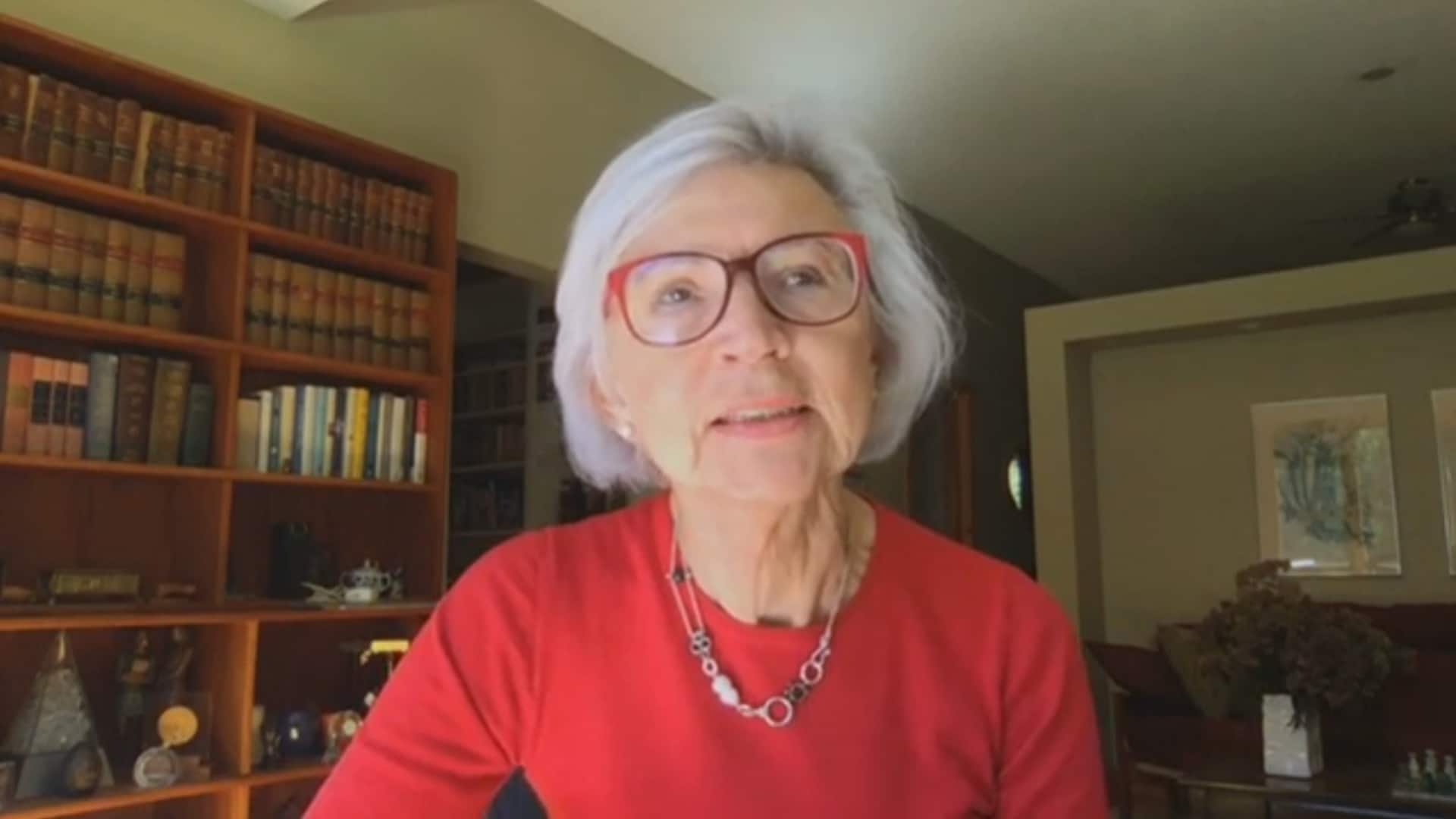

Former Supreme Court of Canada Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin speaks with Michael Serapio about Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s wide-ranging influence. 5:09

It was once widely accepted that judges must, by and large, interpret and apply the law irrespective of their moral compass or personal policy preferences. The idea of judges intently shaping the law according to their personal vision of right and wrong, regardless of what the law actually dictates, was long considered antithetical to the judicial role.

But reactions to Ginsburg’s death, many of which echo Abella’s tribute, and the antipathy directed toward Barrett for her rejection of the view that judges can decide cases based on their comprehensive worldview, suggest that high judicial office is today viewed in a deeply partisan manner by many in Canada and the United States.

Truth be told, attempts to undermine the nomination of Barrett to the U.S. Supreme Court over her religious beliefs were largely a smokescreen. Many of her critics realize that Barrett, a Catholic, will not rule according to the Catechism of the Catholic Church. As for legal qualifications, her sterling reputation and credentials – top of her law school class, clerk to Justice Scalia, distinguished professor, and appellate judge – more than fit the bill.

The reality is that Barrett’s opponents worry that her tenure on the Court will secure the reversal of constitutional precedents on abortion, health care, and other sensitive social issues not because of her religion, but because of how she approaches the tasks of statutory and constitutional interpretation.

Republican Senator Joni Ernst asks U.S. Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett how she would respond to people who say she is not an adequate replacement for the late liberal Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. 2:35

Barrett adheres to schools of interpretation known as textualism and originalism, which seek the law’s meaning at the time it was enacted. Ginsburg adhered to the school of living constitutionalism, which teaches that the meaning of a Constitution can evolve over time. It is a battle not of religion but of judicial philosophy, of how judges ought to go about interpreting the law.

It is one thing to worry about a nation’s constitutional precedents being overruled because you think those precedents are legally sound: that the Constitution, properly interpreted as a law, protects certain rights or permits certain legislation. It is another thing altogether to worry about overruling because you think that certain rights and legislation deserve to be protected or permitted by the Constitution, before you even turn to the legal analysis.

Today many of us look to judges to resolve the latter concern, to be framers rather than guardians of the Constitution, and that is the heart of the matter.

Judges are ultimately responsible for saying what the law is, not what it should be.

Judges are doing something other than judging if they arrive at the legal outcome in a case based on their – and perhaps our – personal worldview.

Judges should be neither liberal nor conservative, nor proponents of any other political ideology or movement. Their allegiance is to the law, and to the law alone. There is much to debate on the matter of judges and judging, but we can all agree on that.

Leave a comment