This story is the third of a three-part series by CBC News and Sports on abuse in amateur sport in Canada. Read the first and second stories in the series.

As the scope of the problem of child sexual abuse in Canadian amateur sports becomes clear, the sports world is left playing catch-up as it tries to revamp safety policies and provide parents with the tools they need to better protect young athletes.

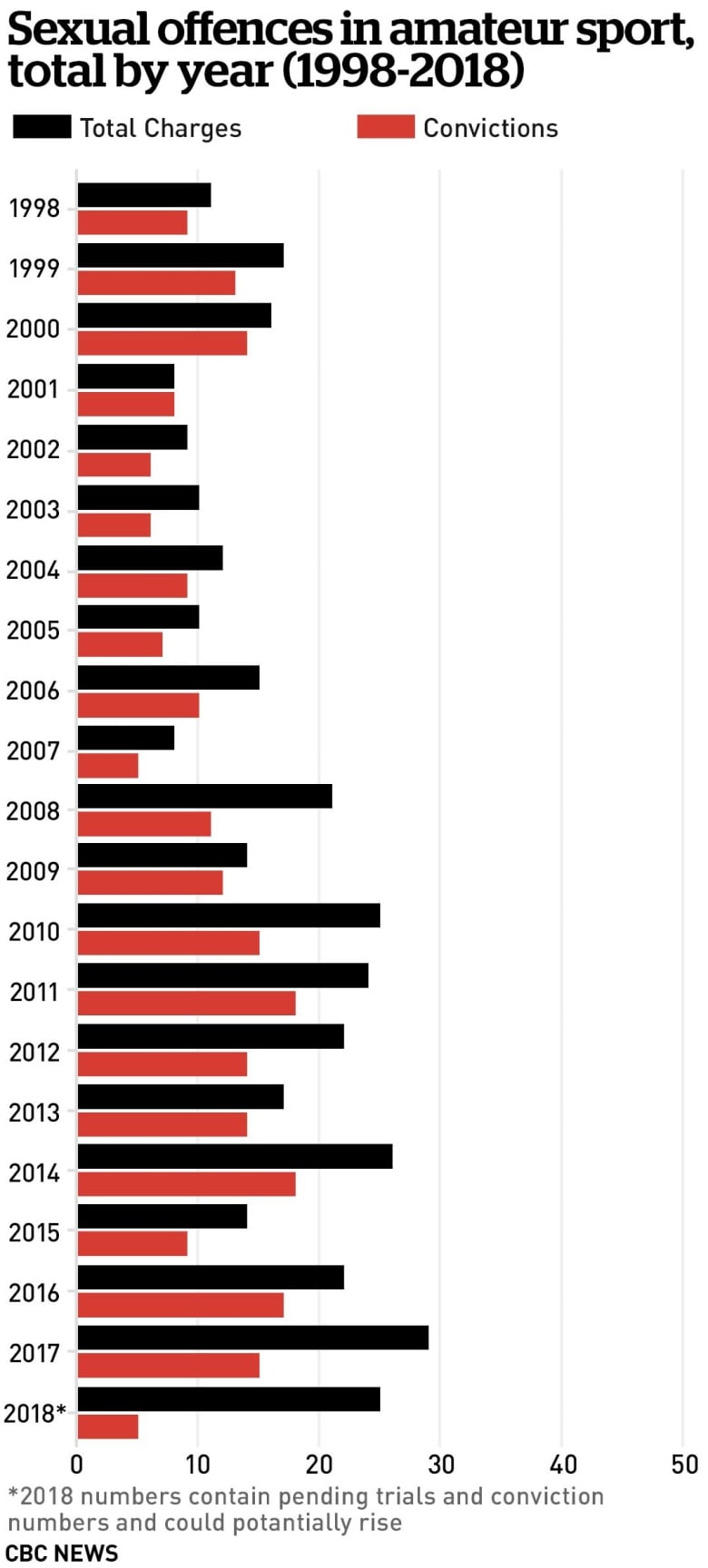

A CBC News and Sports investigation found at least 340 coaches across Canada have been charged with sexual offences against minors in the past 20 years. Of those, 222 coaches have been convicted.

There are currently at least 34 trials against coaches before the courts.

“It breaks my heart that my sport has been looked at in the way that it has. It breaks my heart that there are kids who are hurting,” said Calgary gymnastics mom Kim Shore.

The trial of former Michigan State University and USA Gymnastics doctor Larry Nassar was the tipping point for Shore. A competitive gymnast herself while growing up, Shore watched many of the harrowing stories of abuse shared by more than 150 victims of Nassar. She says it was gut-wrenching but propelled her into action.

But it wasn’t just Nassar’s case that had Shore worried about the future of her sport. Canada was grappling with its own issues — three gymnastics coaches were suspended for sexual assault charges within the span of a few months.

Kim Shore, left, pictured here with her daughter Addison, a competitive gymnast, wasn’t impressed with the resources online for parents looking for tips to keep their children safe in sports. (Jill English/CBC)

Shore, whose 12-year-old daughter, Addison, is a competitive gymnast, went in search of resources to try to arm herself with information on how to detect potential predators.

“To be honest, I started Googling and looking for advice for parents on how to raise an athlete and what initiatives need to be taken to make sports better,” Shore said.

What she found is there wasn’t a lot of information on how a parent should confront coaching abuse.

CBC asked some child protection advocates and sports experts about what local and national sport organizations — and parents — can do to protect children.

Watch Kim Shore discuss her tough conversations with young athletes on The National:

Watch for transgressions

In the era of social media, experts say parents need to be aware of who their child is communicating with online. CBC’s investigation found many cases where abuse was initiated by a coach online.

In Nova Scotia, for example, volleyball coach Joseph Potvin pleaded guilty in September 2011 to sexual exploitation, sexual assault, luring a child and producing child pornography. He was sentenced to four years in prison.

Potvin admitted to grooming a 17-year-old girl he was coaching in Dartmouth using electronic communication, including having sexually explicit webcam chats with her.

This chart shows findings from CBC’s investigation into charges and convictions against Canadian coaches for sexual offences against minors. The breakdown is based on the sports in which the charged coaches were involved. (CBC)

Potvin’s techniques of online manipulation aren’t uncommon, says Noni Classen, director of education at the Canadian Centre for Child Protection. She says coaches are turning to text messaging and social media with more regularity to prey on young athletes.

“If a coach starts to text a child individually 50 times a day and the parent is not clearly on those and is not aware of the correspondence that’s happening … That’s a transgression,” she said.

Classen suggests parents create a joint email address with their child for all communication with a coach. She also says parents should initiate a conversation with coaches early on about proper coach-athlete boundaries.

Toxic power imbalance

When it comes to trying to build young children into sports superstars, parents can sometimes be reluctant to question a coach’s behaviour.

Lorraine Lafrenière, chief executive of the Coaching Association of Canada, says coaches have a privileged position over athletes, which can lead to a toxic power imbalance and potentially even abuse.

-

CBC Investigates

Sex offences against minors: Investigation reveals more than 200 Canadian coaches convicted in last 20 years

-

CBC Investigates

Local sports clubs say they’re left on their own to protect young athletes from abuse

“We think a coach has the gold dust to performance and so therefore we confer all of this trust … that they must be good or that we can’t challenge their authority outside of that, and that’s not OK,” Lafrenière said.

Lorraine Lafrenière, head of the Coaching Association of Canada, has a list of questions she says parents should ask of sport organizations. (CBC)

She says parents can become too focused on their child’s athletic performance and neglect to pay attention for signs of misconduct.

She says parents need to start asking sport organizations questions that go beyond what happens on the field of play. What is the screening process for coaches and staff? Who is responsible for overseeing and enforcing the rules? And what is the policy for reporting abuse?

Background checks not enough

Most sport organizations implemented background checks in the wake of the notorious Graham James case 20 years ago. James is a former junior hockey coach in Western Canada who was convicted of abusing six of his players hundreds of times, including future NHLer Theo Fleury.

But CBC’s analysis of court records found that even in the early 2000s, coaches were still slipping through the cracks.

Take, for example, the case of Gilbert Dubé. He’s a former Montreal North minor league hockey coach who was sentenced to five years in prison for sexually abusing four players on his teams between 2002 and 2009.

But this wasn’t the first conviction for the hockey coach. In 1993, Dubé was convicted of sexual touching. During his second sentencing in April 2011, he suggested Hockey Quebec was to blame for not checking his background thoroughly before allowing him to coach several hockey teams.

At the time, Hockey Quebec said it did have a background-check policy in place, but it was left to the discretion of each local club to implement.

A look at data from CBC’s investigation of charges and convictions against Canadian coaches for sexual offences against minors in the past 20 years. (CBC)

Background checks are essential, but experts say they can’t be the only safeguard.

“We cannot rely on the criminal justice system to be our means of how we’re protecting children,” Classen said.

She says predators are able to slip through the cracks because many victims don’t report abuse until years later. In such cases predators can go undetected because they don’t have a record that would be flagged in a criminal background check.

CBC’s analysis found that one-third of the 340 criminal cases against coaches were brought forward at least a decade after the alleged offences occurred.

WATCH | Former Olympic gymnast Kyle Shewfelt discusses what can be done to reduce the risk of abuse in sport:

Need clear policy

Classen says if a sport organization lacks a clear, formalized conduct policy, it leaves parents in the dark about how to address potential abuse by coaches. She says some parents and athletes may be afraid of retribution because they don’t know where or how to report misconduct.

“It creates silencing,” she said. “It creates problems and it breeds environments for abuse to occur, where people aren’t comfortable with bringing forward concerns.”

Noni Classen, director of education for the Canadian Centre for Child Protection, suggests parents create a joint email address with their child for all communication with a coach. (Jeff Stapleton/CBC)

Nearly every national, provincial and local sport organization in Canada is responsible for conducting its own internal investigations before deciding how to move forward, CBC’s investigation found. The problem with this model, Classen says, is parents don’t have full confidence in a sport organization’s ability to thoroughly investigate its own coaches.

Children can’t protect themselves

Finally, experts say, parents need to speak up immediately when they feel their child is in a compromised spot.

Too often, they say, parents may not notice there is a problem and the onus is then put on the vulnerable athlete to come forward and report their abuser. Classen says there needs to be an ongoing conversation between the child and parent about the young athlete’s relationship with their coach.

“It isn’t up to children to protect themselves,” Classen said. “They can’t compete with an adult who is potentially looking to exploit them or misusing their relationship with them or betraying their trust. It has to be other adults who are questioning what’s going on.”

Here is a list of questions Classen and Lafrenière say parents should be asking when enrolling their children in a sport:

- Does the club have a standalone abuse policy?

- What is the screening process for coaches and staff?

- Do they have a social media policy?

- Who is enforcing the rules?

- What is the policy for reporting abuse?

- Is there a list of coaches who have been suspended or banned?

- Do they have the “rule of two” — more than one adult present with a child at all times?

— With files from Jamie Strashin

Editor’s Note: CBC Sports acknowledges that it has ongoing contractual agreements to produce, broadcast and stream various events with several national sport organizations.

For readers under the age of 18, if you have questions or have ever felt uncomfortable, talk to a parent, guardian or adult you trust. If you don’t have someone you can talk to, call KIDS HELP PHONE at 1-800-668-6868 or live chat them at KidsHelpPhone.ca.

If you have information to share on this story, please contact Lori Ward at lori.ward@cbc.ca or Jamie Strashin at jamie.strashin@cbc.ca. You can also send anonymous tips through CBC Secure Drop.