The daughter of a Kingston, Ont., senior who lost $250,000 after his trusted accountant encouraged him to invest in a “questionable” financial scheme says police did little to investigate when the suspected fraud was reported, despite all kinds of suspicious documents and the loss of the bulk of her father’s retirement savings.

“I approached the [Kingston] police with this evidence and said, ‘There’s something very wrong here,”‘ Diane McEwen-Loveys told Go Public. “Their response was that they couldn’t do anything.”

McEwen-Loveys with her father, Mendal McEwen, who is now suffering from dementia. (Photo submitted by Diane McEwen-Loveys)

A former senior RCMP investigator who now consults on white-collar crimes says McEwen-Loveys’ experience isn’t unusual, adding police often have little financial crime expertise and few resources for such investigations.

“There is a limited pool of investigators with financial crimes experience,” says Greg Draper.

Odd document

McEwen-Loveys says the financial nightmare began in 2016 when her father, Mendal McEwen, had to be placed in long-term care due to dementia.

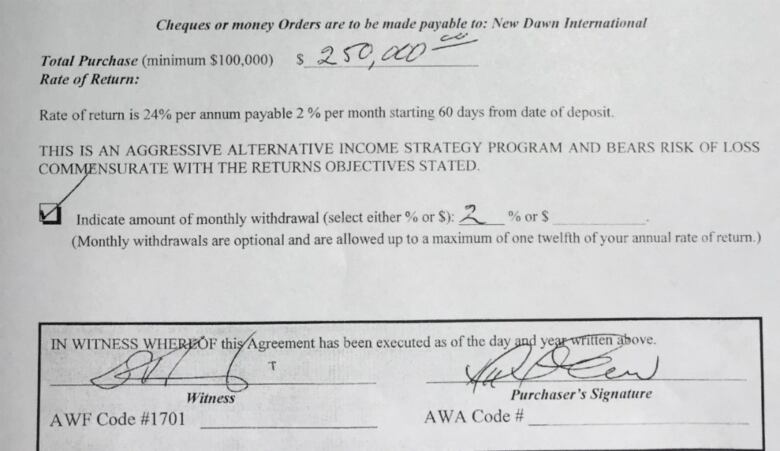

While going through his papers, she discovered a strange-looking “participation agreement” that her father had signed in 2008.

“Standard wording that’s required for that type of documentation was missing,” says McEwen-Loveys, who has a financial background.

“It quickly became clear to me that something was very wrong.”

Her father’s long-time accountant, Douglas Raymond of Kingston, had arranged an agreement with a financial company called New Dawn International — no mention of it can be found online. The document does not explain what type of company New Dawn is, or how McEwan’s money would be used.

The agreement says New Dawn operates in “the Principality of Hutt River,” a small region in western Australia that claims to be an independent, sovereign state.

“What’s going through my mind is, ‘This can’t be a hoax,'” says McEwen-Loveys. “There’s gotta be some reality to this.”

She did a little digging and discovered that the Principality of Hutt River has its own self-declared prince, its own currency, its own stamps and passport — but none of that is recognized by any government.

McEwen invested $250,000 in 2008 and was promised a rate of return of 24 per cent a year, starting 60 days from the date of deposit.

Mendal McEwan committed $250,000 in this agreement brokered by his trusted accountant. (Submitted by Diane McEwen-Loveys)

McEwen-Loveys couldn’t find any paperwork on the agreement — no statements, no prospectus — so she’s not sure what the deal was all about, or what happened after her father handed over a large chunk of his retirement savings.

She did find a record for a wire transfer for $250,000 her father made the same day he signed the agreement, moving money from his registered retirement fund, which resulted in a hefty tax bill.

But it’s not clear who the money was wired to, or where. Banks aren’t required to keep records for longer than seven years.

McEwen-Loveys also discovered two emails from her father to Raymond, in which he asks for some of the money supposedly resulting from his investment.

In 2010, Raymond told his client in an email that “the cash flow is not positive at this point.” In a second email a year later, Raymond wrote: “We are still months away from turning this into a positive situation that can start paying out.”

With suspicions growing, McEwen-Loveys contacted various securities regulators and confirmed that the investment was not registered in Ontario.

She also called the Chartered Professional Accountants of Ontario and learned that Raymond was no longer a registered accountant, and had not been registered when her father made the large withdrawal from his retirement savings.

She decided to call Raymond and record the call.

During the conversation, Raymond said he couldn’t discuss the investment with McEwen-Loveys because “it’s complex” and “complicated.”

Listen to call with the accountant

He told her he couldn’t say where the money is now, because information about the investment “is not available.”

He cut the conversation short, saying, “I’m not going to continue the discussion at this point.”

Go Public wanted to speak further with Raymond, but he did not return calls or emails.

Turns to police

Unable to track down the $250,000, McEwen-Loveys turned to Kingston police.

The case was reviewed by fraud investigators, who determined they couldn’t proceed with a criminal investigation.

In an email to McEwen-Loveys, a constable wrote that the investment scheme was “questionable to say the least,” but because McEwen’s father had dementia he could not be considered “a viable witness/victim.”

Greg Draper, a former RCMP fraud investigator turned forensic accountant, specializes in white-collar crime and says police often don’t have the mandate or resources to investigate complex fraud cases. (CBC)

McEwen-Loveys says investigators told her they didn’t listen to the recording of her call with Raymond, because they couldn’t open the audio file.

“It’s very frustrating,” she says. “The only body that has any authority would be the police. And they were unwilling to take up the case.”

After Go Public contacted Kingston police, they said they were reviewing a fraud report, but could not comment due to confidentiality concerns.

Draper says one of the challenges of investigating possible financial crime is the time required.

“They are document intensive and often it takes several steps — multiple search warrants or interviews, evidence gathering sessions — to get the materials you need,” he says.

“They can take months and years to properly collect everything under the standards that are needed for criminal prosecution.”

Tips for avoiding financial fraud

- If it’s too good to be true, it probably is. High rates of return are a red flag.

- Ask questions: Who is selling the product? Does it make sense?

- Check registration: People selling many financial products need to be registered.

- Be transparent: Talk to your family before making a sizeable investment.

- Never wire money to a stranger.

Help for investors

While looking online for help, McEwen-Loveys came across the Investor Protection Clinic at Toronto’s Osgoode Hall Law School.

Opened last fall, the clinic gives free legal advice to people who believe their investments have been mishandled.

Founder Poonam Puri, an expert in corporate and securities law, says her clinic hears from many people like McEwen-Loveys who were turned away by police.

“Municipal police are really focused on traditional crimes involving physical harm and the things that you would think of when you think of police and crime,” says Puri. “I think the police are less well-equipped to deal with economic crimes.”

Law professor Poonam Puri says the best advice for the elderly to avoid financial fraud is for parents and their adult children to have regular conversations about money matters. (Tina Mackenzie/CBC)

Even when a suspected victim has dementia — as is the case with Mendal McEwen — a case can still be pursued.

“It’s important to hear from the person who’s been harmed if that’s possible,” she says, “but if there’s documentary evidence that tells a story of wrongdoing and harm, that’s equally important and perhaps even more powerful.”

McEwen-Loveys is hoping a team of students at York University’s Investor Protection Clinic — Max Ledger, Eric Cheng and Paniz Ghazanfari — can build a criminal case to get her father’s money back. (Tina Mackenzie/CBC)

McEwen-Loveys has teamed up with three law students at the clinic, including Max Ledger.

“Our goal is to produce a narrative that is compelling,” says Ledger, “and will eventually convince a police officer to look at the case, look at the timeline, look at the evidence and say, ‘This is something I think we should pursue.'”

McEwen-Loveys says it’s not about the money anymore.

“I see my father being victimized, and I don’t want that happening to anyone,” she says. “At this point, it’s really about ensuring this doesn’t happen to others.”