As the 25th anniversary of the Premier League nears, the FC crew discuss how the league has changed over a quarter century.

The Exploding Heads provide their comical take of what exactly will happen this Premier League season.

Football often finds itself in nostalgic mood for something or other. This summer marks the quarter-century of the advent of the Premier League, the all-consuming behemoth that has been blamed for everything from ticket prices to the ongoing failures of the England national team.

The comprehensive rebranding and rebooting of the top flight is also cited as a much-maligned bookmark in the history of the game, something the “football wasn’t invented in 1992” pedants have been railing against ever since. But the very same summer witnessed another development whose anniversary is very rarely celebrated and whose financial impact can’t be measured, but which transformed football — overwhelmingly for the better — overnight.

The backpass law was the boldest move instituted by the game’s rulemakers, the International Football Association Board (IFAB), to combat the growing cynicism with which goalkeepers were being used.

“The goalkeeper has a rare privilege in football,” wrote FIFA in an unusually opinionated press release. “The use of his hands to keep the ball out of his goal, which would otherwise be virtually impossible. But it is a privilege that should not be abused.”

The notably goal-shy World Cup of Italia ’90 is regarded as the paragon of cynical football — a tournament that climaxed with two red cards and a late penalty to decide its winner — and IFAB were admirably quick to home in on a potential solution to salvage elite football as a spectacle.

Law 12, Section 2, which prohibited goalkeepers from handling any deliberate pass from a teammate’s boot, was scheduled to come into immediate effect after the European Championship of 1992. Peter Schmeichel and Denmark duly gave this particular strand of gamesmanship a rousing send-off in the final against Germany as they completed their otherwise heroic and unexpected triumph.

In retrospect, this is actually quite impressive in its almost total lack of shame. Weeks before the brave new world of the backpass law, Germany’s Jurgen Klinsmann dutifully jogs after the ball, without complaint, in full knowledge of the fact that Schmeichel would simply pick it up, give it a few bounces and then hoof it up the field. And repeat. In the final seconds, German defender Stefan Reuter slid the ball back to Bodo Illgner, and earned the dubious consolation honour of performing the last legally handled backpass in a major tournament.

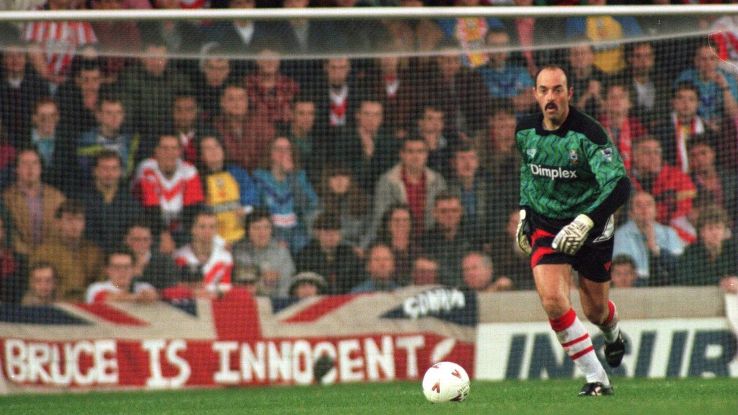

The early 1990s changes to the rules meant a lot of nervous dribbling for goalies like Bruce Grobbelaar.

The early 1990s changes to the rules meant a lot of nervous dribbling for goalies like Bruce Grobbelaar.

As has so often been the case with tweaks to the Laws of the Game over the past 150 years, goalkeepers had the most to worry about with the new rule. From a spectator’s perspective, even if the game was likely to speed up, the biggest fear must have been that absent-minded own goals such as Lee Dixon’s inch-perfect lob over David Seaman would become extinct.

The early days were a steep learning curve for everyone. Nottingham Forest defender Brian Laws used the pre-season Makita Tournament as an experiment by kneeling down and heading the ball back to his goalkeeper Mark Crossley; within days, FIFA were forced to make clear that any obvious attempts to exploit loopholes in the new law would come under the umbrella of “unsporting behaviour.”

The 1992 Olympics would be football’s first official engagement with the backpass law. It took less than an hour to secure its first victim: Italian goalkeeper Francesco Antonioli hadn’t done his homework and the USA’s Joe-Max Moore thumped home the indirect free-kick from 15 yards. The early stages of the 1992 Charity Shield between Leeds and Liverpool were a tense affair, with everyone waiting for the first chance to see Bruce Grobbelaar and John Lukic deal with an official examination of their footballing skills.

A terrified Lukic boomed the ball into the Wembley stands at the first time of asking and commentator Andy Gray remained sceptical about the whole thing: “I just think that is the perfect example regarding it… is that making the game any better, when you see the goalkeeper under pressure like that, just lumping the ball out of play? I don’t think so.”

That set the tone for an equally nervous opening weekend to the new Premier League even if the top flight’s new identity was still grabbing all the attention.

“After all the hype and hullabaloo, it was just as we expected,” wrote the Independent on the opening day of the 1992-93 season. “A classic case of the emperor’s clothes. No matter how the promotions spielers dress it up, the new Premier League is merely the old First Division by another name.”

Aside from the logos and shiny new kits, though, the game had been visibly shaken up on the field. The first few weeks of the season were characterised by centre-backs and goalkeepers engaging in some sort of nervous little dance before one of them decided that the ball would be better off in Row K for the moment.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NPG76gDDEIk&w=560&h=315]

Things clearly had to get a little worse before they got better for the long term but that left a huge opportunity for sheer footballing slapstick in those innocent, wide-eyed months of late 1992. In September, Sheffield United travelled to White Hart Lane to face Tottenham and their poor goalkeeper Simon Tracey would manage to sum up the mild chaos of the immediate post-backpass chaos in the space of 15 utterly brilliant seconds.

It begins with a simple enough backpass, which Tracey contrives to turn into a one-man tragicomedy.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IO3O4gVQaas&w=560&h=315]

To summarise, then:

1. decent first touch

2. highly inadvisable decision to try and dummy and then outrun the opposition winger

3. run the ball straight out of play

4. unsuccessful and undignified attempt to wrestle the ball from a small child

5. rugby-tackle an opponent who is trying to take the quick throw-in, approximately six inches away from the linesman

Even apparently “under-control” situations between goalkeeper and defender were at the mercy of early-1990s playing surfaces — and the fact that the defender in question was sometimes Frank Sinclair:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hs0EMsnHPGU&w=560&h=315]

Huge lessons were learned from these anxious few months of 1992-93, and it hastened the obsolescence of goalkeepers who simply couldn’t play football, followed gradually after by the phasing out of old-school defenders who had previously been happy to leave the fancy stuff to their number 10.

The enforced evolution of goalkeeping has led to the concept of “sweeper keepers” to the point where they have arguably become the new playmakers. That is perhaps the one response to the backpass law that FIFA hadn’t anticipated — “it was never really foreseen for the goalkeeper to be the planner and initiator of attacks,” they had previously declared — even if the primary goal of making football quicker and more attractive has almost certainly been achieved.

With its physiques and fitness levels to match, breathless modern football is scarcely recognisable from the stop-start-pause-for-breath spectacle that forced IFAB’s hand at the start of the 1990s. With the luxury of hindsight, you even begin to wonder how any team lost a lead late in a game when they had the watertight safety device of passing back to their goalkeeper as often as they wished in order to run the clock down.

The other seismic developments in 1992 — and the 25th anniversary retrospectives we’ve read this week — have succeeded in obscuring just how immediately effective the backpass law was. Tweaking the fabric of football is hardly a straightforward exercise — the Bosman ruling proved that in 1995, and the tentative moves toward VAR continue to do so — but the backpass rule represented a classic example of the lawmakers making the right call at the right time.

FIFA, for once, had relayed the message loud and clear: “After all, football is essentially a game of skill and there is no skill in simply standing there, holding the ball in one’s hands.”

No, football wasn’t invented in 1992. But, while the Premier League proved to be a multi-million-pound distraction, football was being thoroughly reinvented.

Adam Hurrey analyses the language of football. You can follow him on Twitter: @FootballCliches.